‘When you’re getting in the way, call it a day’: Mitchell & Webb vs New Statesman on assisted suicide

An article in The New Statesman this week was entitled ‘Let them die: the case for assisted dying’. Its author, political journalist Oli Dugmore, best known as editor of men’s website JOE.co.uk, gave an astonishingly one-sided take of the issue of assisted suicide, which failed to engage with any concerns and simply declared that legalisation is in everyone’s best interests.

Dugmore was writing in the midst of the House of Lord’s Second Reading of Kim Leadbeater’s assisted suicide Bill.

The second day of debate takes place today. According to Upper House convention, it will pass without a vote and undergo line-by-line scrutiny at Committee Stage.

‘Let them die’

He starts with a classic straw man fallacy, painting a picture of someone with motor neurone disease, who will gradually deteriorate until they are completely dependent on the people around them to survive. He implies that all in such a position would want their death to be hastened by lethal drugs.

He then compares the act of a doctor giving such drugs to a suicidal patient who may have years left to live to a soldier firing a bullet to end the suffering of a catastrophically wounded friend. He suggests the former is less of a moral quandary.

And while he dismisses any religious opposition out of hand, Dugmore claims two other arguments are persuasive. Firstly, the British public is getting older while the number of taxpayers is shrinking. Assisted suicide would mean fewer payouts for end-of-life care, NHS treatments, and pensions. For Dugmore this is unquestionably a positive.

And secondly, autonomy: “no-one else knows what’s best for you. You are the single greatest arbiter, the one who should decide your future, lack of it, and means of getting there. I wouldn’t dream of telling you how to live your life, so why should I tell you how to end it?”

He later says assisted suicide is no different to signing a Do Not Resuscitate order, but his most egregious comments come in his final remarks.

“All over the country our elders sit in cell blocks bathed in the stupefying light and sound of Bargain Hunt, Location, Location, Location, Tipping Point, unvisited by relatives who are preoccupied by the rhythm of their lives, or perhaps unable to summon the courage to witness the degeneration of the once totemic figures of their lives, their mum and dad. Let them die.”

Unpicking arguments

The callousness is staggering. As is the total lack of appreciation that those on the other side of the argument, who believe assisted suicide would be a disaster for British society, have a plethora of reasons for opposing its legalisation.

While Christians do believe in the sanctity of life – that we are all made in God’s image and are worthy of dignity and respect – there are plenty of other secular reasons and arguments which cannot be brushed aside.

Taking Dugmore’s MND patient as an example, there are many disabled people, those with degenerative illnesses and otherwise, who oppose assisted suicide. More broadly, Leadbeater’s Bill would grant assisted suicide to terminally ill adults deemed to have less than six months to live. But doctors and nurses specialising in end-of-life medicine routinely say it is almost impossible to accurately predict when someone will die. Their predictions are frequently too short.

Dame Esther Rantzen, one of the leading proponents of assisted suicide, has stage-four lung cancer. She was thought to have only weeks to live, but two years later she is still living thanks to a ‘wonder drug’ that has allowed her more time with her family making precious memories both with and for them. In December last year, she wrote of ten reasons she’s happy to still be alive, although her campaign to allow a hastened death continues.

Stephanus Breytenbach, an Australian man, told The Christian Institute that when he was diagnosed with stage-four pancreatic cancer and was told he likely had only weeks to live, he might have chosen assisted suicide had it been legal at that time. Not long after, his wife was diagnosed with cancer and while he made a remarkable recovery, she passed away quickly. Had he chosen assisted suicide, his two teenage children would have been left orphaned.

Financial burden

There is Dugmore’s other argument, of course, which is that assisted suicide would benefit the country financially, as well as be beneficial for individuals’ families.

He posits: “I know many, many people in their middle age who, when conversation turns to older age, and death, sing the refrain: ‘Just let me go, I don’t want to be a burden.’ They view it as a simple economic equation, many of them having put their own parents through care homes, and then hospitals and hospices, as their estates and lifeforce drain away.

“It’s an interesting parental reflex: would you rather spend the significant wealth accrued in your house on palliative care and extensive medical treatments or, instead, end your life early and guarantee an inheritance for your progeny?”

This argument though is a double-edged sword, for it hangs on the idea of being a burden on others. Many campaigners have often highlighted that a so-called ‘choice to die’ could very quickly become a ‘duty to die’.

‘When you’re getting in the way, call it a day’

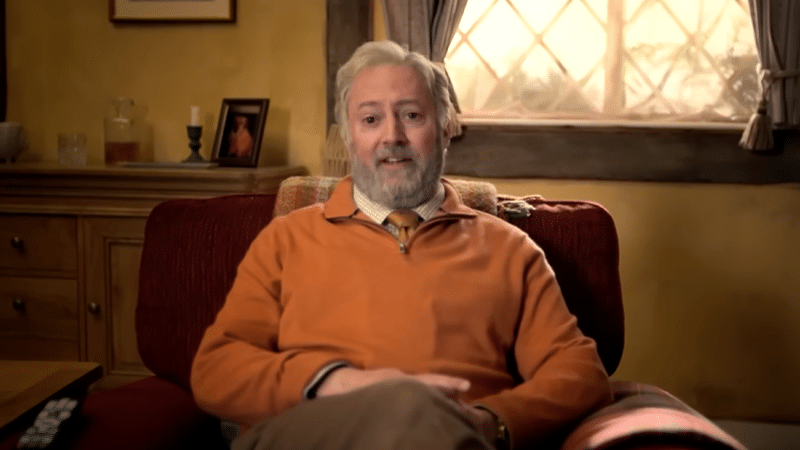

Few make this argument so clearly as a recent sketch in Channel 4’s Mitchell and Webb Are Not Helping, in what Telegraph columnist Michael Deacon described as “the most blistering piece of satire I’ve seen in years”.

The full sketch, which contains strong language, is titled ‘Assisted Dying Advert’, and sees David Mitchell tells viewers in a soothing, comforting voice that if they have lost control of their bodily functions, they should “consider the Deathlitas ‘Cut Your Losses’ plan”.

“For a reasonable price, you can pay the ultimate price, and your loved ones will have the peace of mind of knowing that they can start getting your smell out of all that lovely property equity.

“Meanwhile, you check into one of our luxurious clinic-cum-crematoria, kick back in a joint-and-muscle-soothing motorised recliner – our nurses humourously refer to them as ‘electric chairs’, though of course you’ll be killed by poison injection.”

In a similarly saccharine tone, Robert Webb provides the voiceover slogan at the end: “Deathlitas. When you’re getting in the way, call it a day.”

The easily-missed small print also reads “Paid over 240 months, inclusive of VAT, miscellaneous fees and dignity”, adding “Free sympathy and sad face emojis upon application”, and “Deathlitas is a trading name for Reaper Insurance”.

Romans 1

It is only satire for now, but the sketch could prove prescient.

Under Kim Leadbeater’s Bill, adverts for assisted suicide will theoretically be prohibited, but a loophole will exist allowing the creation and distribution of literature in doctors’ waiting rooms, for example. They may not use the same script as David Mitchell and Robert Webb, but the underlying messages will be the same. ‘Don’t be a burden. Do the decent thing and die.’

Proponents of assisted suicide have largely tried to hide their utilitarian motives. Instead they have deliberately opted to champion ‘autonomy’ and ‘choice’ and preach ‘compassion’ for those with terminal illnesses – all the while ignoring the much larger group of people with no wish to die, but who will inevitably feel pressured to end their lives.

This is what Romans 1 tells us to expect. When society rejects God, they will call good evil and evil good.

We must pray for our society to return to God and embrace his good design for the world, which we know is good for all people – regardless of what Oli Dugmore might believe.

More on assisted suicide:

External: New Statesman criticised for suggesting assisted dying would save money