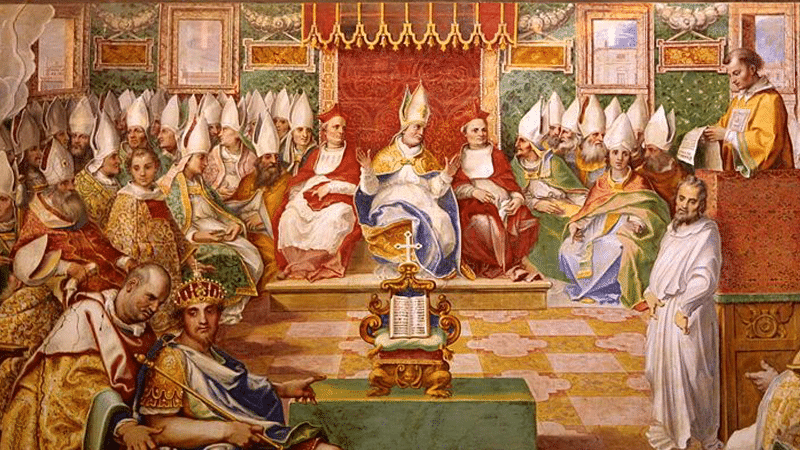

A ‘praiseworthy landmark’ as the Council of Nicaea marks its 1,700th anniversary

COMMENT

The Council of Nicaea in the year 325 was, arguably, the most theologically significant and influential gathering of Christians in post-apostolic church history. Martin Luther called it ‘the best and first general synod after that held by the holy apostles’. It produced a creed which, in the revised form sanctioned by the Council of Constantinople in the year 381, was soon being recited in all the churches as an act of worship. In many traditions it is still recited today.

Before the Council of Nicaea met, there had been many local church councils, but none of universal extent. However, the theological issues at stake in the early 4th century were felt to be of such magnitude that only a universal council (representing all Christians) could make a proper response. Those issues revolved around the person of Christ. Everyone acknowledged that he was the pre-existing Son of God who had become human to redeem humanity. But who or what exactly was the Son of God? Was he the first and greatest of God’s creations? Or was he of the same nature as his Father – equally and eternally God?

Muddy waters

It would not be difficult to show that the more traditional view in the church was the latter of these, that the Son is fully and truly God, existing on the Creator’s side of the Creator-creation divide. However, the theological waters had been greatly muddied in the 3rd century by a view known as Modalism or Sabellianism (after Sabellius, its chief architect, who flourished in Rome in the early 200s). Modalism affirmed the full deity of Father, Son, and Spirit. But it denied their personal distinction. They were simply three ‘modes’ or manifestations of one divine person, who appeared as the Father in Old Testament times, as the Son during the incarnation, and as the Spirit at Pentecost and in the life of the church.

The greatest energies of orthodox theologians in the 3rd century, therefore, were devoted to proving that real personal distinctions existed between Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. By far the most impactful of the 3rd century theologians who wrote on this was Origen of Alexandria. Almost all Greek-speaking Christians entered the 4th century with a profound reverence for Origen as a kind of ‘master teacher’.

Origen, however, left a mixed heritage. While he was eminently successful in demonstrating the reality of personal distinctions in the Godhead, he also taught that the Son was not as fully God as the Father. He did not think the Son was a created being. But he thought that when the Son eternally ‘radiated’ from the Father’s essence, as light from light, the Son lost a degree of the Father’s original perfect brightness. This meant that Origen had secured the personal distinction between Father and Son at the cost of making the Son inferior to the Father.

Arian controversy

As the 4th century dawned, another Alexandrian theologian named Arius expounded a radical modification of Origen’s view. Arius argued that the Son’s inferiority to the Father required that the Son should be considered a created being. The Son was the first, highest, and noblest of the Father’s creations; in and through the Son, the Father created all other things, and related to them through the Son’s mediation. But the Father alone was true God – eternal, uncreated, immutable, and almighty.

Arius was a presbyter and a popular preacher in the Alexandrian church, and his eloquence convinced many. However, his bishop, Alexander, was a full-blooded Trinitarian, and tried to silence Arius through disciplinary action. He summoned a local Egyptian council in 320, which deposed Arius for heresy. But Arius was a pugnacious individual, unprepared to give up without a fight. He succeeded in canvassing a large measure of support from other Middle Eastern bishops by persuading them that he was simply defending Origen’s legacy of the Son’s inferiority to the Father.

Arius depicted Alexander as challenging that legacy by his refusal to accept Arius’s beliefs. In fact, he accused Alexander of the dreaded error of Modalism. Ominously, Arius proved a masterful propagandist in his own cause. The result was increasing division in the Eastern Greek-speaking church, and increasing theological confusion about the real character of the Arius-Alexander dispute.

Emperor Constantine

This was the situation when, in the year 324, Constantine became Emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire. He had already been Emperor of the West since 312. Now the fortunes of war had also delivered the Eastern Empire into his capable hands. Constantine was a professing Christian – the first Emperor to acknowledge Christianity as the true faith. Moreover, whatever deficiencies a later generation might have found in him, Constantine had a very genuine devotion to the wellbeing of the church.

Constantine was utterly appalled by the disunity and controversy he found among the Eastern Christians. Feeling it his duty to do anything he could towards restoring church unity, and advised by his close counsellor, the Spanish bishop Hosius of Cordova, Constantine made a momentous decision. The best way to end the unedifying controversy was, he resolved, by means of a great gathering of bishops and presbyters from throughout the Empire, who could deliberate on the issues and arrive at a collective judgment.

Constantine therefore sent Hosius to Alexandria, empowering him to summon the Empire-wide church’s ordained officers to meet together in the city of Nicaea (now Iznik in Turkey) in north-western Asia Minor. Constantine chose Nicaea for logistical reasons: it was close to the Eastern imperial capital of Nicomedia and well located on the nexus of Roman roads for Christians from throughout the Empire to travel there. We are not sure how many bishops made the journey; the traditional figure, according to Athanasius of Alexandria, is 318, which may not be far wrong.

Council begins

The Council opened in the imperial palace at Nicaea in May or June 325. Constantine himself attended, and his entrance marked the commencement of proceedings. Although the Emperor was present, he did not actively control the Council; its chairman seems to have been Hosius of Cordova. The centrepiece of the Nicene Council’s business was the Arian controversy. Arius was allowed to participate, and he read out a written confession of his faith.

This proved a spectacular misfire: most of the bishops were horrified by Arius’s forthright denial of the Son’s deity and assertion of his creaturehood. One bishop was so disgusted, he snatched the confession from Arius’s hands and tore it to pieces. A later tradition famously describes how bishop Nicholas of Myra (the historical figure behind Father Christmas) punched Arius in the face and had to be disciplined for his excessive zeal.

Since Arius could quote Scripture with as much fluency as any man, the Council decided that it had to set forth the orthodox interpretation of Scripture – an interpretation that Arius and his followers could not sign without obvious and gross hypocrisy. The outcome was a creed, drafted by a committee, and then discussed and debated by the Council on a statement-by-statement basis. One delegate who distinguished himself by his forceful biblical arguments for the Son’s full deity was Athanasius, the young personal secretary of Alexander of Alexandria.

Athanasius would succeed Alexander in the bishopric in 326 and be the foremost antagonist of the Arians until his death in 373. Probably no ‘saint’, down through the ages, has attracted more admiration among Christians of all types than Athanasius. Calvin hailed him as ‘the chief defender of the orthodox faith, a divine writer worthy of immortal praise, the good Athanasius of ancient times’.

Finalised text

The finalised creed was then signed by all but two of the bishops, Secundus of Ptolemais and Theonas of Marmarica (convinced Arians). One sometimes reads, in ill-informed non-Christian literature, that the deity of Christ was decided at Nicaea ‘by a close vote’. This is an absurd myth. The decision was made by an absolutely overwhelming majority – by 316 to 2, if we accept Athanasius’s figure of 318 bishops being present. The two Arian dissenters, along with Arius himself, were sent into exile by Constantine. The text of the Creed of Nicaea says:

We believe in one God,

The Father almighty,

Maker of all things, seen and unseen;

And in one Lord Jesus Christ,

The Son of God,

Begotten of the Father,

Only-begotten,

That is, from the essence of the Father,

God from God,

Light from light,

True God from true God,

Begotten, not created,

Of the same essence as the Father,

Through whom [i.e., through the Son] all things were created

Both in heaven and on earth;

Who for us humans and for our salvation

Came down and was incarnate,

Became man,

Suffered and rose again on the third day,

Ascended into heaven,

And will come again to judge the living and the dead;

And we believe in the Holy Spirit.

(We should note that the Nicene Creed, as recited today, is the product of the Council of Constantinople in 381, whose creed was a sort of revised version of the original Creed of Nicaea, with a much expanded section on the Holy Spirit.)

‘Same essence’

The key term in the Creed was homoousios, Greek for ‘of the same essence’. By affirming that the Son is of the same essence as the Father, the Creed was ascribing deity to the Son in the most absolute and explicit manner. The ‘essence’ (ousia) of a thing refers to its innermost reality. Therefore, whatever God the Father is in his fundamental being or nature, the Son is the same: equally eternal, almighty, all-knowing, all-holy, and the proper object of worship. The only difference between Father and Son lies not in their nature, but in the way they possess it – one Fatherwise, the other Sonwise. But their essence is identical. At one stroke, the word homoousios excluded Arianism from any and all legitimate existence in the church.

To the Creed, the Nicene Council attached a series of ‘anathemas’ (from Galatians 1:8-9) aimed at Arian beliefs in the created nature of the Son.

Paradoxically, the Nicene Council did not definitively settle the Arian controversy, which would bubble on for another 50 years. Arians showed themselves remarkably adept at dividing true believers against each other, and at manipulating the machinery of the state in their own favour. It would not be until the second of the universal Councils, the Council of Constantinople in 381, that Arianism was finally defeated and driven out of the church. But Constantinople did this by building on foundations laid at Nicaea; the second Council is unthinkable without the first.

Easter dates

The Arian controversy was not the sole issue dealt with by the Council. There had been a long-running controversy between different geographical regions of the church about the correct date on which to celebrate Easter. The Council settled this controversy, affirming the position championed by the churches of Alexandria and Rome, the leading churches of East and West.

The controversy is excessively complicated to describe, but it was essentially between those who wanted to bind the church to a strict observance of the traditional Jewish calendar (principally the church in Syria), and those (principally the churches of Alexandria and Rome, but most other Christians too) who argued that the traditional Jewish calendar was an unsound guide in accurately calculating time.

The Council’s verdict in favour of the majority view championed by Alexandria and Rome means that, throughout the world today, Easter is observed according to the principles adopted at Nicaea. The only major difference today is that the Orthodox churches of the East still use the Old Julian Calendar to calculate Easter, whereas Roman Catholics and Protestants use the newer Gregorian Calendar, which are 13 days out of synch. But they all use the same principles within each calendar – principles derived from Nicaea.

Long-term consequences

What were the long-term consequences of the Council of Nicaea? It bore a rich and powerful testimony to the church’s historic belief in the deity of Christ. The bishops at Nicaea were not debating some strange new issue; they saw themselves as defending and vindicating the way that the church had always understood the teaching of the apostles, enshrined in Holy Scripture.

He who saves humanity must necessarily be God, since God alone can save. For denying this, Arius was condemned and cast out as a heretical innovator. This runs contrary to so much modern narrative that paints the Fathers of the Nicene Council as the innovators, and a non-divine Christ as the earliest object of belief. History reveals a different story.

Nicaea also entrenched the principle that controversies among the professing people of God should be settled by conference and council. The church universal would follow this principle for the next thousand years. Church history is unintelligible without it. Even though Protestants have never had a universal Protestant Council, they have often tried to follow conciliar principles – think of the Synod of Dort and the Westminster Assembly. This is worth reflecting on in our often individualistic church culture.

Church and state

Nicaea also cemented the fledgling church-state partnership that had come into being through Constantine’s conversion to Christianity. It had always been understood, in Roman imperial tradition, that the Emperor should use his authority to foster the worship of the gods. Constantine had a new God, but he still thought as a Roman Emperor. He therefore devoted himself to doing everything he could to help the church: ensuring its liberty in his own Empire, advocating for its liberty in other lands, protecting it from persecution, facilitating its unity amid debilitating controversy, and incorporating its values into his social legislation.

There was, however, a sinister downside to this. When Constantine exiled Arius and the two Arian bishops after Nicaea, this established the principle that the Christian political power could punish people for heresy. Here was a seed that would grow into the intolerant, persecuting Christendom of the Middle Ages, and its immediate aftermath in early Protestantism, which shed the blood of so many believers deemed to be ‘heretics’.

Praiseworthy landmark

The Council of Nicaea, then, while it does not partake of sinless perfection in every aspect, nonetheless remains a basically good and praiseworthy landmark in the unfolding history of the church. Those who study the Scriptures on the subject of Christ’s person will find in its pages what the Nicene Council faithfully set forth.

As Calvin said of Nicaea and some of the succeeding Councils, ‘We willingly acknowledge, and revere as sacred, the early Councils, to the extent that they concern the teachings of the faith, such as those of Nicaea, Constantinople, the First Council of Ephesus, Chalcedon, and so forth, which met to overthrow falsehoods. For they contain nothing but the wholesome and authentic exposition of Scripture, embraced by the holy fathers with spiritual wisdom in order to vanquish the enemies of godliness who had at that time emerged’ (Institutes 4:9:8).

This article first appeared in Evangelical Times.

Revd Dr Nick Needham writes and edits theology material for The Christian Institute. He lectures in church history at Highland Theological College and is the author of the five volume series: 2,000 Years of Christ’s Power.

By Nick Needham, Theology Editor